Metal Bedsteads for Prince and Peasant

18th December 2018

A century ago, Birmingham showed the world how to make metal bedsteads. Linked with the city’s thriving brass-foundering and metal working industries bedstead making developed into one of Birmingham’s most profitable trades with a worldwide export market. In the late Victorian period the brass bedstead with its curtains, intricate fancy work and mother of pearl decorations, was stocked by all the leading house-furnishers and coveted alike by the prosperous citizen and the Indian Maharaja as a tangible sign of affluence.

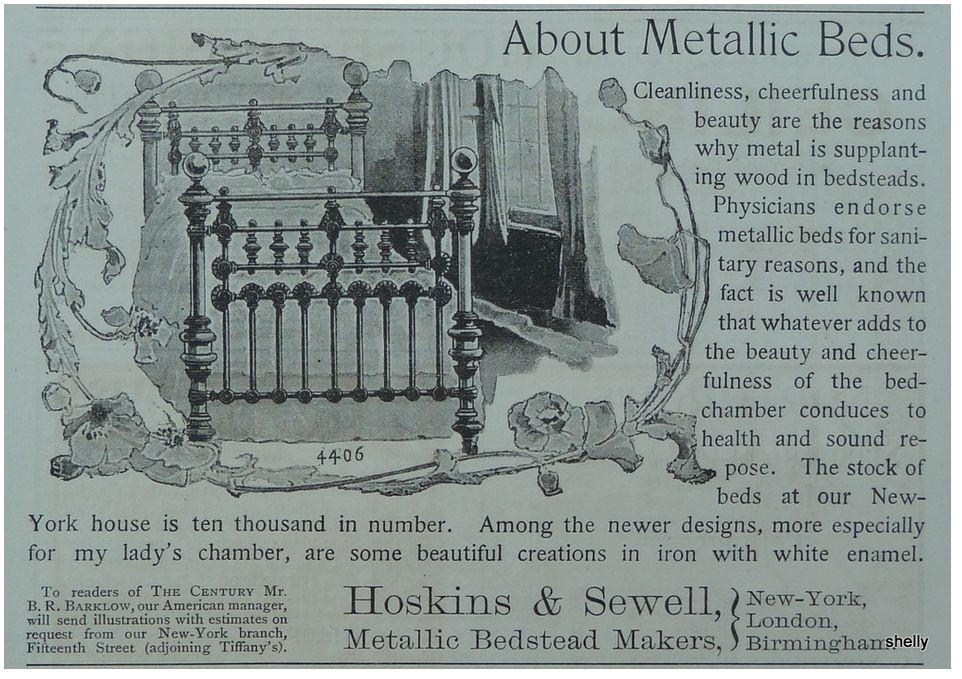

Birmingham remains the British centre of this trade, and the headquarters and most of the member firms of the Metallic Bedstead Association are in the city and district. A pioneer bedstead firm, and one of the largest in the world, is Hoskins & Sewell, which was founded on its present site in Bordesley in 1846. Thousands of city bound travellers are intrigued daily by the signs on the Bordesley works – “Ships berths”, “Brass and Metal Beds”, “Metal Windows” – a trio of assorted enterprises which seems to be a microcosm of Birmingham’s industrial diversity.

The company makes metal bedsteads of all kinds, from simple army and utility models to complex hospital and surgical beds, equipped with a wealth of adjustable components to cater for the comfort of the patient and to meet medical and surgical requirements. Made far from the sea, the company’s ships berths, in hundreds of different forms, sail the oceans of the world in ships of almost every nation. Metal window frames are made for homes, offices ships, and public buildings from Midlands to Mombasa. The firm’s catalogues of several thousand standard lines include also a wide range of hospital equipment – screens, trolleys, stands, lockers and aseptic furniture – as well as tubular steel tables and chairs.

The variety of tastes in bedsteads attests the importance of an article of furniture on which we pass on third of our lives, and the company has always striven to cater for the most exacting individual requirements – however inconvenient to production processes. A bedstead 7ft 6in long was once made to accommodate the giant frame of Primo Carnera. A brass bed 13ft square was designed for the communal repose of an eastern potentate and 11 of his wives and servants. Another Oriental ruler demanded a bed made of silver, and silver fillings had to be swept up for safekeeping after each day’s work on this rare order. Richly decorated metal and brass bedsteads, long outmoded at home, are still made in large similar numbers for export to the West Indies, South America, Cyprus, Mauritius, and the Near and Fareast, where they favoured for their decorative and insect resisting qualities.

Until the early nineteenth century, metal bedsteads were made of solid wrought iron, an expensive process in which joints were formed by heating and forging the metal. The modern metal bedstead industry was made possible when Dr Church, of Birmingham, patented the chilled casting, by which dovetail joints could be cast in “stocks” or moulding boxes fitted round the intersections of tubular frame members. The new process was first taken up by Peyton, Hoyland & Peyton Ltd, which was founded in 1839 and amalgamated with Hoskins & Sewell. Chilled castings and the use of tubes revolutionised the efficiency of bedstead making, and Birmingham brass founders co-operated with bedstead designers to indulge the Victorian taste for heavy and lavish decoration.

Four-poster bedsteads were made with elaborate cornices and galleries containing scores of brass spindles and bosses, pearl and mirror boxes and Gothic decorations of cast brass. Sometimes even clocks were fitted, to face the bed head. Similar ornamentation was applied to “half testers” in which a curtain rail was mounted on pillars above the head; to the late Victorian “Italian” type of bed, with straight curtain rails projecting from each head pillar; and the galleries at the head and foot of the “French” bedstead, which had short pillars and no upper-work. Babies slept in cots and bassinettes of like magnificence.

The brass bedstead reached it’s zenith with a 15ft high four poster specimen with which the company won the highest award at the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893. A vast American eagle surmounted it, and the innumerable decorations included a 2ft high replica of The Statue of Liberty in cast brass. The company’s present four-poster catalogue illustrates several hundred types made only for export. The latest export consignment of all brass bedsteads went to Nigeria in December, no doubt for the use of tribal chiefs. Popular in many countries is the metal four-poster with brass ornaments, and round black enamelled pillars decorated with floral patterns.

The manufacture of ship’s berths was begun about 1900. Each shipping line and each nation has its own particular requirements for crew and passengers, and every berth must be individually designed to conform with the bulkheads and other furniture shown in the plans of the ships draughtsman. Many nations are now increasing the comfort of ship’s crews by providing individual or two berth cabins, with enamelled steel cots instead of galvanised steel berths grouped together. Every berth is vermin proofed by the use of seamless tubes, and many first class berths are finished in chromium plate, oxidised silver, or brass.

The company has achieved a high reputation for its hospital equipment and production has been increased to cater for the demands of the National Health Service. A recent appliance, the “Oxford” maternity table, embodies the latest developments in obstetric practice and is already in use in at least 50 British hospitals.

The raw materials of bedstead making are steel and brass tubes, pig iron for castings, and wire for mattresses. Pig iron is continuously smelted in small blast furnaces. The bedsteads are assembled on trestle frames, with “stocks” fitted at the joints. Into the stocks molten metal is poured from hand ladles to form chilled castings. After dipping in deep baths of paint, or spaying with air guns, the frames, heads, and foot ends are dried in drying ovens.

Wire mattresses are assembled by girls who skilfully link springs and V-shaped wires into a strong, diamond shaped tracery. There are many other forms of spring mattresses, including interlacing steel laths, woven wire, and combinations of wire and conical springs and of springs and chains. Beds are exported at a rate of thousands a month in knock down form while for the home market “combination” beds are made in three sections – head, foot and frame and mattress – with chilled casting dovetail joints.

The company has representatives in Malta, The Gold Coast, Newfoundland, several South American States, India, Burma, Mauritius, and South Africa. Skilled and patient hand craftsmanship ensures the highest standard of quality, and many of the 350 employees have spent a lifetime with the company.

In homes and hospitals, liners and tramp steamers, and barracks and maharaja’s palaces, the quality and designs of Hoskins and Sewell products show that Birmingham, which pioneered the metal bedstead trade, is still the leader.

Source: Birmingham Post Newspaper